New home for mastodon bones a true display of PFW school spirit

By Blake Sebring

August 20, 2024

Two years after starting college in 1980, Jon Havens declared geology as his major with no idea of the everlasting impact his decision would have on Purdue University Fort Wayne. Neither did Haven’s friend, Dan Brinkman, or Mike Stoller, who graduated in 2018, and more recently Whitney Hadley-Salay, B.A. ’23, but their efforts are now prominently reflected on campus in a display that should endure for generations to come.

These are four students representing dozens who helped showcase and preserve the original mastodon bones from which the university gets its nickname. A display of the bones was mounted last week in the hallway that leads to the International Ballroom and near the new Herd Hideout at Walb Student Union.

The bones resided at Kettler Hall from 1984 to 2016 until being removed during a renovation. Ever since, there’s been a behind-the-scenes push to build another public display, with Ben Dattilo, professor of geology, and Scott Bergeson, assistant professor of biology, as the de facto caretakers.

During the 2022-23 academic year, Student Government Association leaders agreed to spend $200,000 in capital funding to help the cause. The Purdue Fort Wayne Foundation also supported the effort with a $20,000 donation.

After being unearthed on a Steuben County farm in 1968, the bones were moved to campus under the direction of Jack Sunderman, who formed the Department of Geology in 1965. They sat on metal shelves in a Kettler classroom and laboratory, available for students to study. Havens loved hearing how Sunderman and his team recovered the skeleton from the farmer’s peat bog.

Geology students Brinkman and Havens once discussed displaying the bones, with Brinkman mentioning they could appear as they would after the flesh had decayed. However, only about 65-70% of the bones had been recovered, and replacing them in a reconstruction would have come with a huge price tag.

Still, Brinkman’s idea inspired Havens to build a balsa-wood model of how everything might look when laid flat. He picked up small animal bones alongside a railroad track for realism, then designed a display case that included spots for placards and places to showcase other artifacts.

Sunderman took the model to Chancellor Joseph Giusti in 1984 to get approval to move forward with the project, and a display was built from Haven’s model. James Farlow, a geology professor, helped place the bones, and the showcase was revealed later that year.

By then, Havens was serving as a teaching assistant. He still has his original model and is now the Irving Materials company geologist, working throughout the state. Brinkman works at Yale University Peabody Museum of Natural History in the division of vertebrate paleontology.

After Sunderman and Farlow had retired, the display at Kettler lasted until 2016, when Dattilo was given limited time to move the bones. Dattilo immediately called for help, and students and faculty rescued the bones to an archaeology lab.

“There was a bunch of students pulling stuff out, trying to be careful and not break the skull,” Dattilo said.

Stoller was one of those students and a part of the mastodon’s next phase. After University of Michigan professor and mastodon expert Daniel Fisher briefly examined the bones in 2016, the university agreed he could have some for further study, with Stoller driving them to Ann Arbor.

“It was a big cargo van,” Stoller said. “We had to carefully wrap them and make sure to use lots of padding and cardboard.”

Dattilo and Farlow arranged for Stoller to intern at Michigan and essentially serve as the mastodon’s caretaker, helping inventory, clean, position, and piece the bones together. He also took photos used to develop 3D models. Stoller spent 2½ years on the project and now works at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, where he handles artifacts for major displays. He also kept close tabs on the mastodon bones and the display plans.

“Especially considering it is the mascot, the face of the university, it will be really cool to give her a proper display,” Stoller said in January.

After the bones were removed from Kettler, Hadley-Salay was one of the students charged with cataloging and storing them. She was known to volunteer for any extra projects, and that’s how Dattilo found her and asked if she could create a 1/12th-scale model he could use to help propose a new display.

Getting the 3D printing of the bones from Stoller’s photos, Hadley-Salay started trimming the “tags” off the plastic pieces, meaning her fingers were constantly sliced and in need of bandages. The work lasted four months and was used as the model for the permanent case.

“To be a part of putting her back on display as she should be is awesome,” Hadley-Salay said. “Being able to work with something so prominent and important to the university—what more can a student do than say they worked on literally the icon of the university?”

The finished project is now ready for all to see—and the timing of might be perfect.

U.S. Sen. Mike Braun, who is now running for Indiana governor, helped introduce the bipartisan National Fossil Act in January with U.S. Sen. Gary Peters of Michigan. That piece of legislation was passed by the Senate on July 29. Hoping for passage in the House of Representatives and a signature from the president, the goal is to designate the mastodon as America’s national fossil.

After sleeping for approximately 13,000 years before being discovered on a Steuben County farm in 1968, the mastodon bones that give Purdue University Fort Wayne its nickname are now standing tall in Walb Student Union. To view all photos in this gallery, click on the very top of the first image below and then scroll through the series to see how this journey has been visually documented through the years.

The original mastodon bones were excavated from a Steuben County farm in 1968.

Professor Jack Sunderman shows the mastodon skull with its massive teeth to three unidentified school children in 1978.

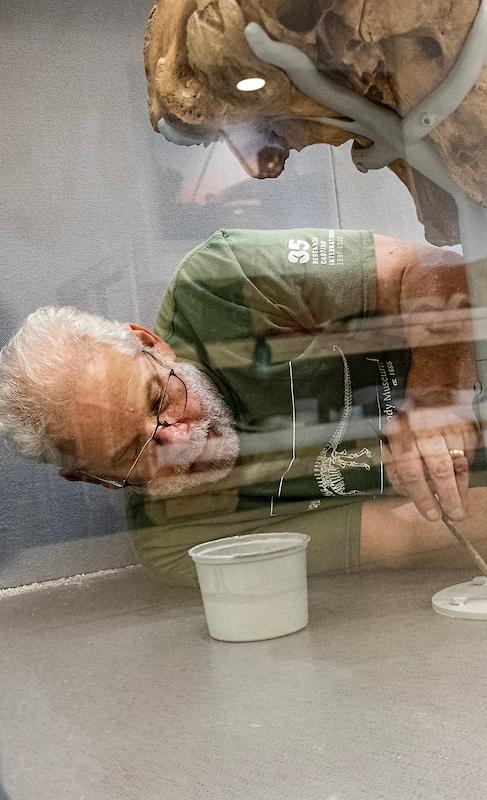

The original display case for the bones was designed by student Jon Havens and revealed in 1984.

The Mastodon bones were prepared in August, 2023 for transport to Ontario’s Research Casting International for preparation for the current display.

The mastodon bones arrived safely at RCI in Trenton, Ontario on Sept. 5, 2023. RCI created the steel mounts for displaying the Mastodon.

Mike Thom of Trenton, Ontario’s Research Casting International, right, and Garth Dallman, begin unloading the mastodon bones on Monday morning, Aug. 12.

Research Casting International from Trenton, Ontario, created forms to place and secure the mastodon bones in the display case.

The mastodon bones were packed on Aug. 22, 2023 for shipment to Trenton, Ontario, where they would be coated for mounting in a new display case.

The bones were carefully identified and packed so they could be removed in order to be placed in the display.

Graham Fredrick, library systems specialist, was part of a team including Erika Mann, director of library technology and digital initiatives, and Daniel Lin, information services technician, who scanned the baby mastodon’s skull for 3D digitization.

Some of the foot bones from “Donna,” the original mastodon bones that give the university its nickname.

Lynn Herbst, Student Government Association vice president in 2022-23, helped spearhead a motion to raise $200,000 from student senate to complete the new display.

Not so fast, Fido, those bones may look tasty but they are not for you to chew on!

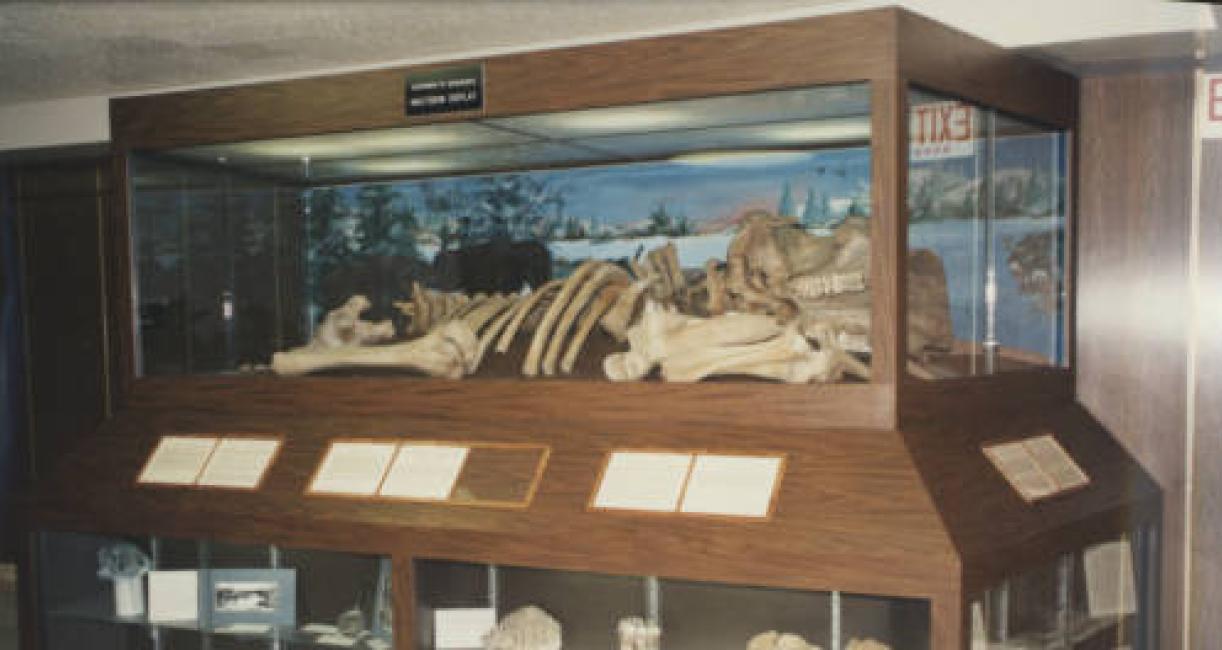

Ben Dattilo, professor of geology, has been the driving force behind getting the new display for the mastodon bones since they were removed from a previous display in 2016.

Mike Thom of Research Casting International, left, and Garth Dallman precisely place the left front foot of Donna for the display on Tuesday, Aug. 13.

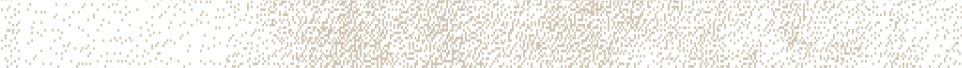

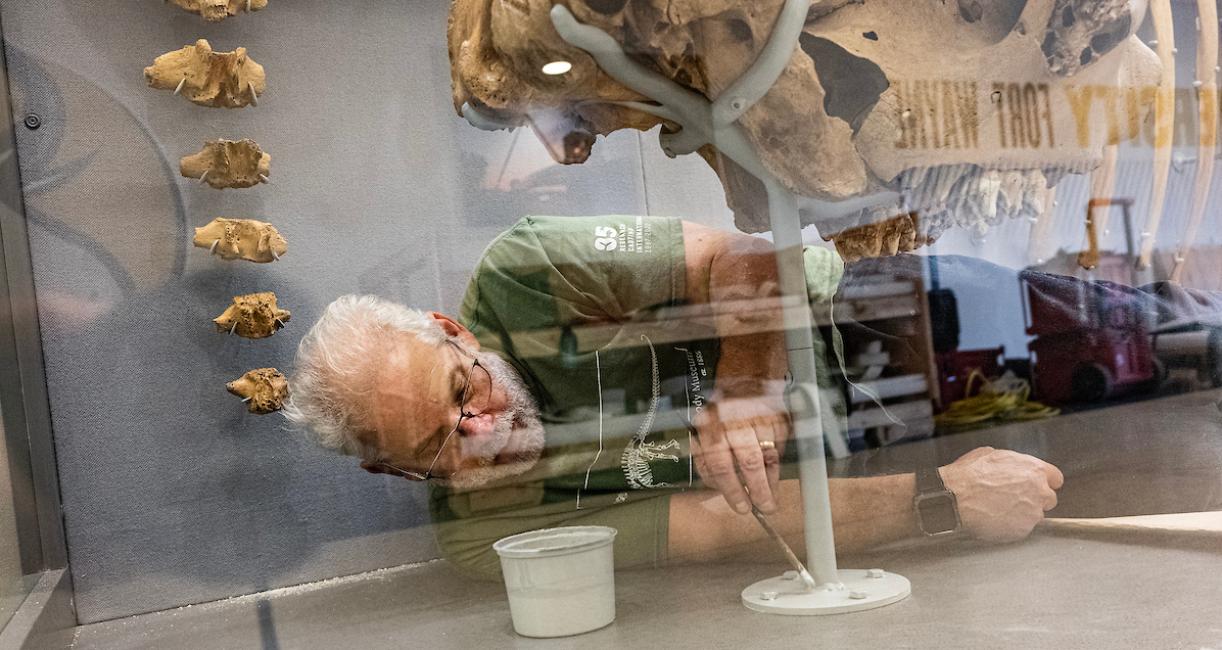

Garth Dallman, part of the skeleton crew mounting Donna in the display, works on the spine from inside the case.

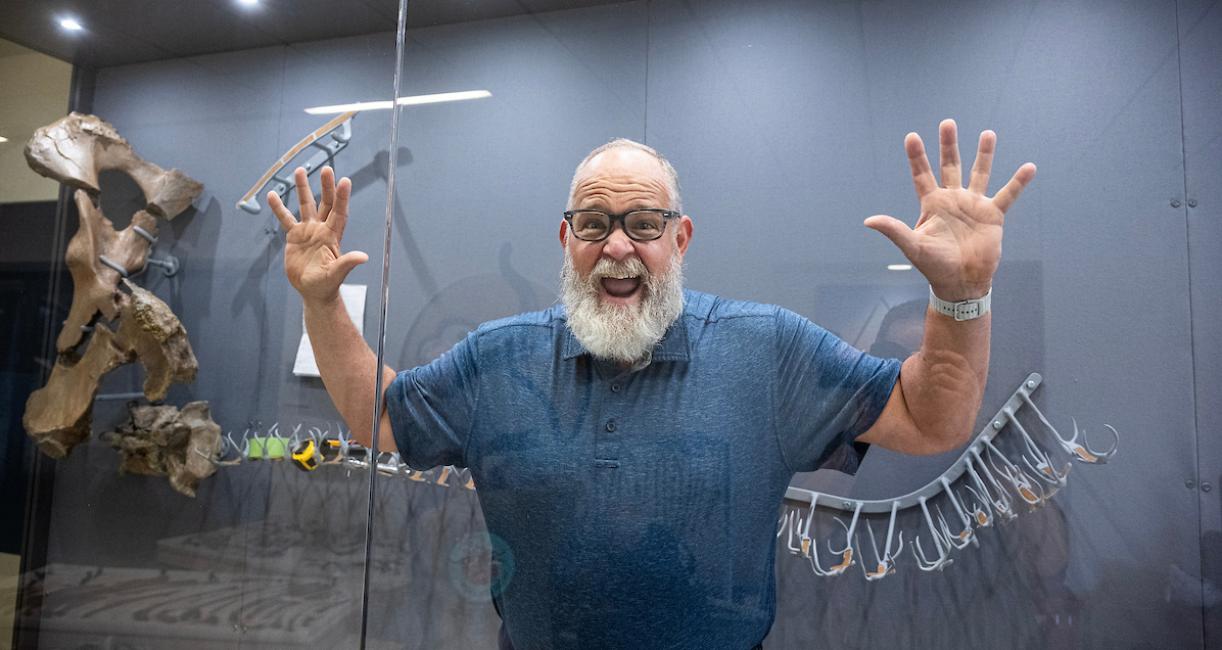

James Farlow, adjunct professor, played a huge role in caretaking for the mastodon after the retirement of Jack Sunderman, who formed the Department of Geology in 1965.

One way to tell Donna was in her late teens or slightly older at the time of her death is by studying her teeth.

Dallman paints over the screws securing Edgar’s skull mounting.

During the two days it took to mount the display, hundreds of PFW employees stopped by with many returning several times during the process to check on progress.

From left to right, Research Casting International’s Mike Thom, Ben Dattilo, professor of geology, and James Farlow, adjunct professor, examine some of the bones during a break.

Placement of Edgar’s skull took various considerations to provide the best angle.

Thom and Dallman move the skull of Edgar into the case. Edgar was found at the same location as Donna, but there’s no definitive answer if he was Donna’s offspring, though she did give birth to two calves.

After eight years of being stored in the basement of Walb Student Union, the 14,000-year-old body of Donna is once again brought back to life in a modern display.