An array of mastodon bones are tagged and ready for transport.

Mastodon bones being assembled for transport.

Mastodon bones being assembled for transport.

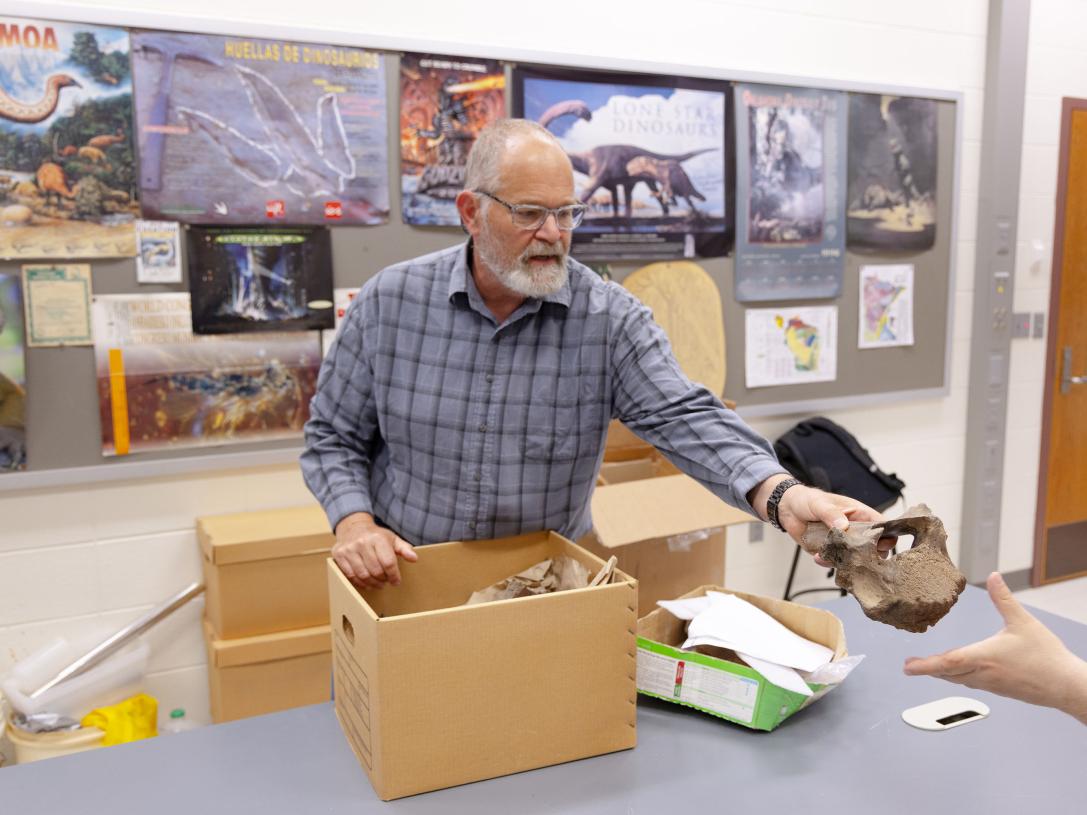

James Farlow, emeritus professor of geology and adjunct professor of biology, prepares a large mastodon bone for transport.

Original mastodon bones returning for campus display

By Blake Sebring

January 30, 2024

After sleeping for approximately 14,000 years before being discovered on a Steuben County farm in 1968, the mastodon bones that give Purdue University Fort Wayne its nickname have been tucked away for the last half-decade. Coinciding with the school’s 60th anniversary, PFW’s original Don is on track to stand tall again later this semester.

The bones were displayed in Kettler Hall from 1984 to 2016 until being removed during a building renovation. Most were examined, wrapped carefully, and hidden away, while parts were sent for further study to the University of Michigan two years later.

Ever since, there’s been a behind-the-scenes push to build another public display. Ben Dattilo, professor of geology, and Scott Bergeson, assistant professor of biology, have been the de facto caretakers, but gaining momentum for the project was difficult.

During the 2022-23 academic year, Student Government Association leaders pushed through $200,000 in capital funding for a first-floor display case near the International Ballroom at Walb Student Union. The tentative goal is to complete the mastodon’s enshrinement in April.

“There has always been an awareness within the student body of mastodon bones, but it’s always just been considered folklore among us,” said recently graduated SGA Vice President Lynn Herbst-Acevedo. B.A. ‘23. “We wanted the true mascot and spirit of the mastodon to be on display. It wasn’t just about us and the legacy we left behind, but the true spirit of the mastodon.”

And the mascot’s story continues to grow. Relatively recently it was discovered that the bones are from a “Donna” and not actually a “Don.” She was approximately 20 years old at death and had calved twice based on a study of her teeth. There was also the skull of a 2-year-old baby, given the name Edgar, found in the same bog. Investigators believe it’s likely, but not certain, that Edgar was her baby.

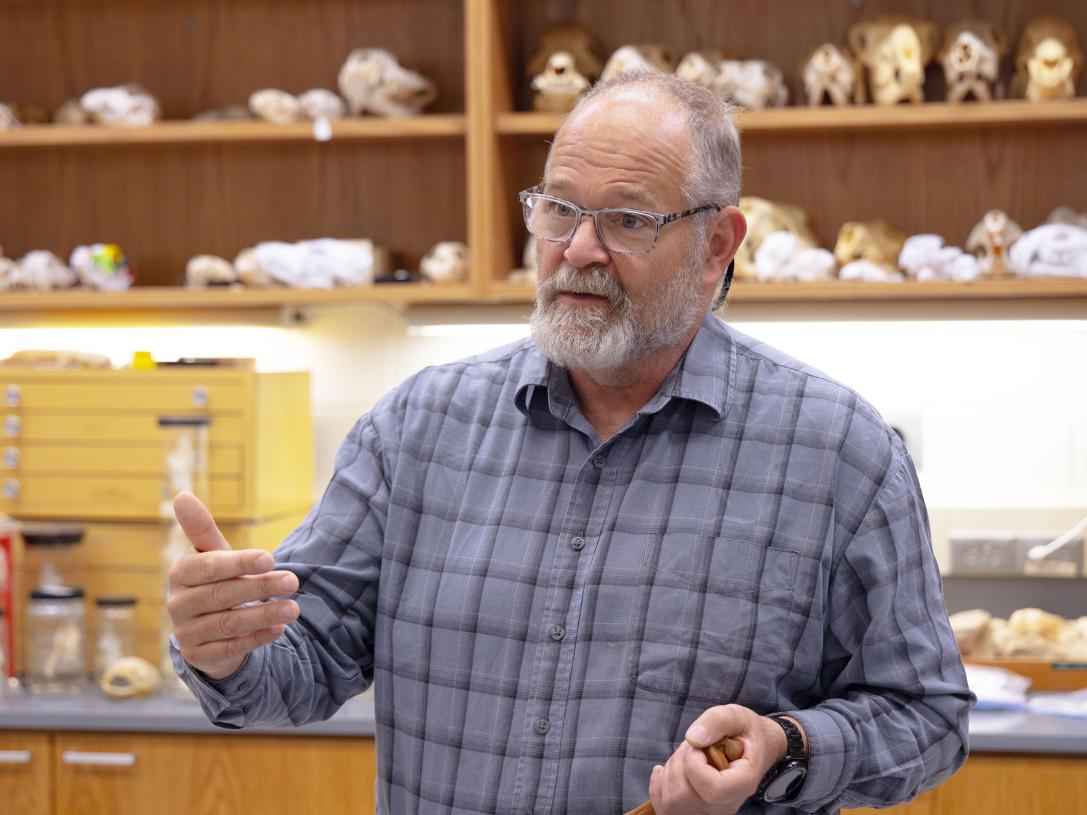

According to James Farlow, an emeritus professor of geology and adjunct professor of biology at PFW who retired from full-time teaching in 2015, she weighed between two and four tons—approximately the same size as the bronze statue of a male dedicated on Alumni Plaza in 2005. A full-grown male would weigh between five and six tons, Farlow said.

“I started talking to people years ago about a display, and we actually got some estimates, and then COVID hit,” Farlow said. “We don’t have all of the limb bones. We don’t have the lower jaw for it, so if you wanted to try to fabricate the missing elements and do a complete mount of the skeleton, you’re talking some serious money.”

An original reconstruction estimate of $400,000 is why the mastodon was previously displayed as a forensic mount where the skeleton was laid flat. The current plan is for a panel forensic mount on the back wall of the display, with the bones positioned in order which will be easier to see.

As a young female, the mastodon is an extremely rare discovery, meaning missing bones would have to be replicated from 3D scans of male or older female bones, adding additional cost to the reconstruction. Along with the lower jaw, Donna is missing 2½ legs, several ribs, and most of the bones in her feet.

The current theory is that the mastodon was killed by hunters and stored in the bottom of a pond to serve as refrigeration. Northern Indiana was covered with ponds before the Ice Age killed off the mastodons approximately 10,000 years ago. Those ponds became today’s peat bogs.

Farmer Orcie Routsong discovered the bones in 1968. He contacted Jack Sunderman who had formed the Department of Geology in 1965, and faculty and students brought the bones to Fort Wayne where they were studied and stored on classroom shelves.

In a letter to the student newspaper the same year the bones arrived on campus, Steve Pettyjohn, then student body president, suggested mastodon as the school’s nickname. A student government committee agreed and it all became official in 1969.

Responsibility for the bones moved from the retiring Sunderman in 1995 to Farlow, and in 2015 to Dattilo, with Bergeson joining the project in 2017. Dattilo said a feature of the new display is that the bones will be removable for further study as technology evolves.

“Her purpose transcends, and it’s the spirit of the thing,” Dattilo said. “I’ve thought about her for quite a while, and this is an irreplaceable legacy. In a sense, it holds the soul of the university.”